Sometimes I do a deep dive “beyond the borders” of Brooklyn Heights. Here’s one of those stories.

A Twitter contact asked me if I knew the back-story of the four Park Slope streets that dog-leg across Fifth Avenue.

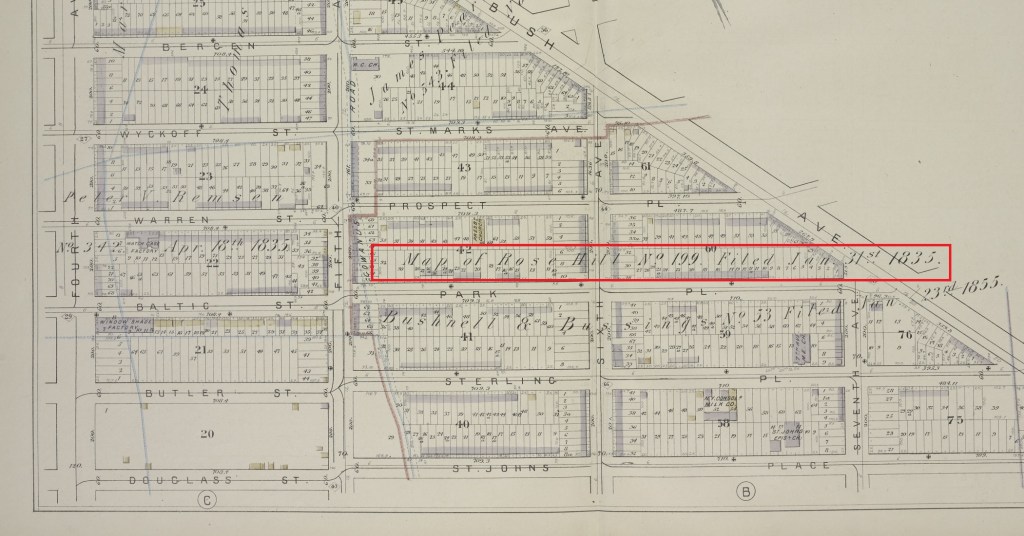

Take a look:

Sure enough, these four streets – Warren, Baltic, Butler and Douglass – each have a 30-to-40 foot northward jump as they cross Fifth Avenue from the west side to the east side. All of the other streets in the area’s grid are continuous when they cross Fifth Ave.

I noticed these dog-leg streets a long time ago. As a pedestrian, I’ve navigated the tricky diagonal crosswalks going from one side of Fifth Ave to the other. Baltic and Douglass are the worst: you can be in the crosswalk heading west, and have a car coming straight at you, driving on the eastbound street from Fourth Ave approaching Fifth Ave, before the car turns parallel to you just as it enters the intersection.

But I never looked into why these streets were like this.

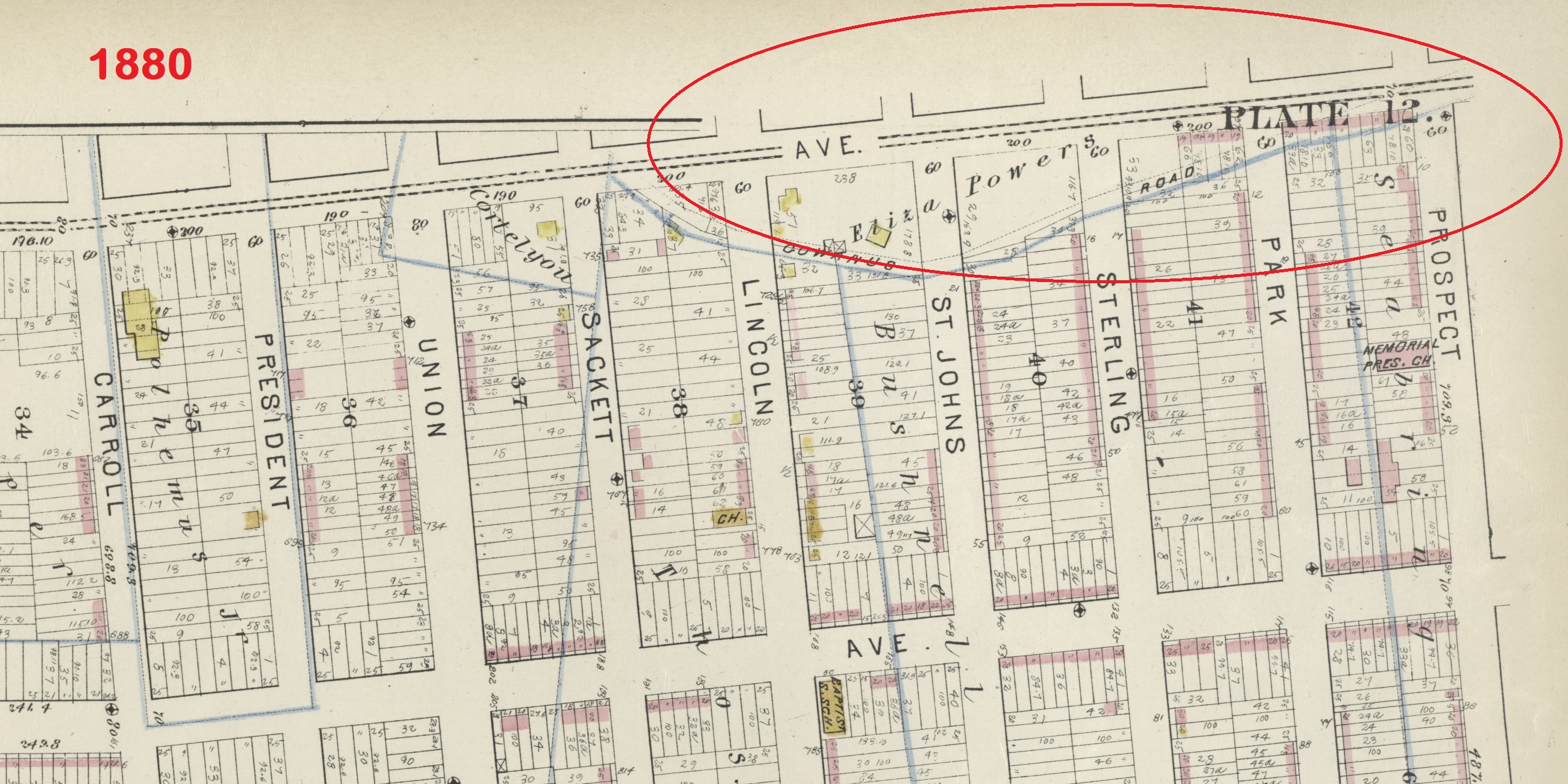

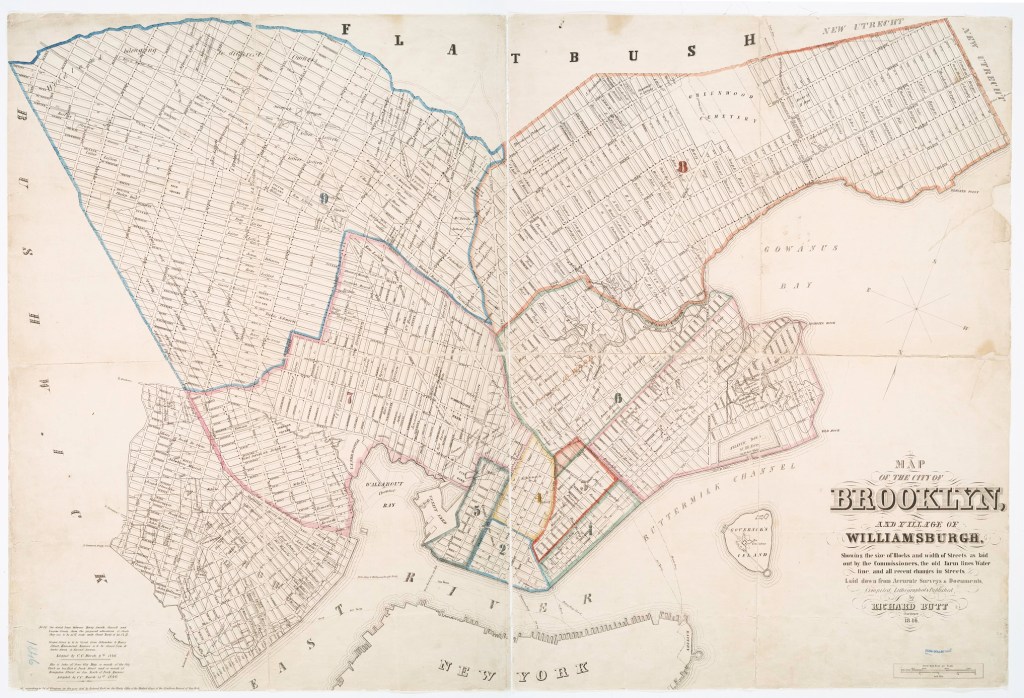

My contact sent two good clues: a so-called “farm line atlas” map from 1880 that shows today’s dog-leg street configuration for those four streets was already in place by then, and a map from 1850 showing those four streets laid out straight like all the others in the surrounding grid. The two maps confirm a couple things: 1. someone CHANGED the original grid, and 2. book-ended dates for when the change occurred.

More importantly, the farm line atlas itself is a reminder that most irregular Brooklyn street paths and boundary lines have their origins in the old farm plots that pre-date the street grid. The first pieces of Brooklyn’s current street grid date to around 1800, but most of the farms shown in the atlas were laid out in the 1600s and 1700s. And many of those farm boundaries themselves were established on the basis of much older Lenape paths and markers.

So a farm line atlas is usually the right place to start for this kind of puzzle. My contact sent me an image from Bromley’s 1880 “Atlas of the Entire City of Brooklyn” which included old farm lines superimposed on the contemporary map.

But there’s another 1880 atlas that’s one of my go-to sources to explain weird boundaries. The Hopkins “Detailed Estate and Old Farm Line Atlas of The City of Brooklyn” is the inverse of the Bromley map: it uses the old farms as its base layer, with the contemporary grid superimposed on top. Most interestingly, the map includes other information about the farms in addition to their boundary lines – metadata!

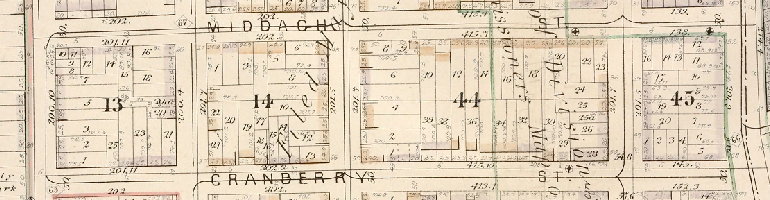

So looking at Vol. 4, Plate A in the Hopkins Old Farm Line Atlas, we see Park Slope’s four oddball dog-leg streets. The map’s 1880 date doesn’t tell us anything new. But notice how the four streets are all within the boundaries of something labeled “Map of Rose Hill No. 199 Filed Jan 31st 1835” – that’s the next clue.

Full 1880 Hopkins Vol. 4, map plate A here.

The italicized labels on the Old Farm Line Atlas maps refer to other maps that had been filed with the county clerk, generally when someone wanted to make a land subdivision. The owner or developer would file a map showing the lots and streets inside their planned subdivision.

Unfortunately almost none of these maps filed with the Kings County clerk’s office have been digitized or are even publicly available. (There are copies sitting in a municipal sub-basement in downtown Brooklyn but getting access is a story for a different blog post.)

However, I don’t think we need to see the Rose Hill map to figure out this puzzle. Probably wouldn’t even help because it’d likely only show streets within the subdivision plot but no reference to streets outside. The boundary of Rose Hill as shown on the Old Farm Line Atlas map is the eastern side of Fifth Ave. Even if you looked at the actual Rose Hill map, my guess is that you wouldn’t be able to see what’s going on with the streets on the western side of Fifth Ave.

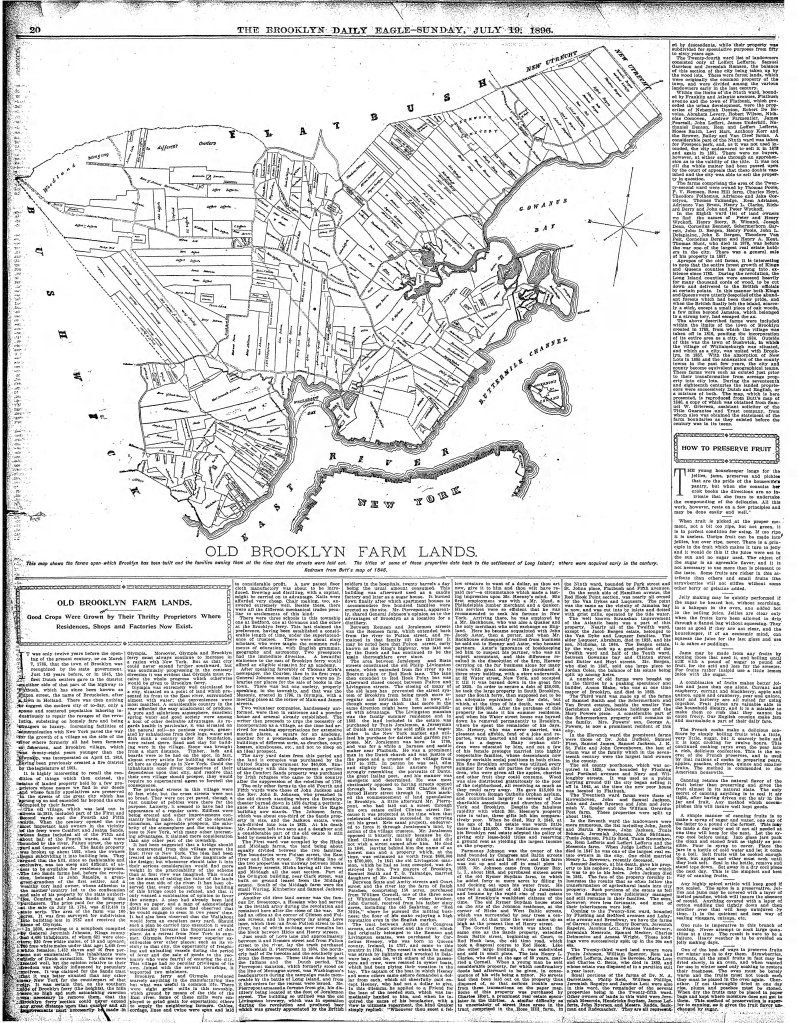

So I consulted another go-source about the old Brooklyn farms – this 1896 article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle titled “Old Brooklyn Farm Lands.” The Eagle piece was written to commemorate the 50th anniversary of ANOTHER farm line map (the 1846 Butt map which I discuss further down). The article highlights all sorts of interesting factoids and trivia about Brooklyn real estate, neighborhood and development boundaries, and streets.

Bingo! There’s a reference to the Rose Hill farm in here – in a section talking about developers and speculators putting together these subdivision maps, and selling building lots off them, before the actual streets were opened up, sometimes leading to discrepancies. One of the examples: “Difficulty as to the uncertainty of street lines arose in the tract comprised in the Rose Hill farm.” These are our four dog-leg streets.

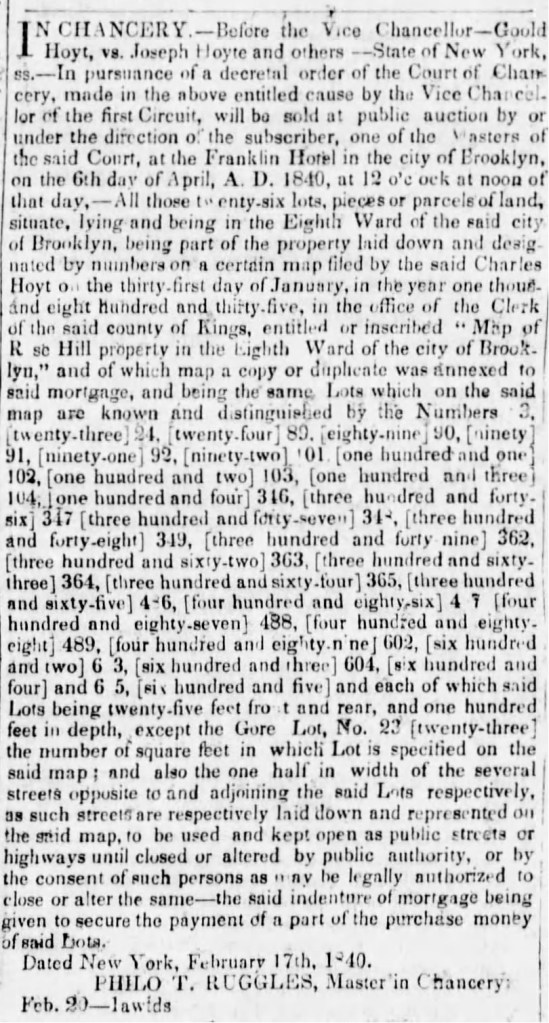

Further searching on the term “Rose Hill” itself in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle archives led me to some earlier hits in 1840 referring to the 1835 subdivision map, mentioning that it had been filed by Charles Hoyt.

(Hoyt was actually mentioned in the 1896 article too, but as described there, his connection to Rose Hill was ambiguous. It did say he was a “a prominent real estate speculator in the thirties,” which I already knew from researching his transactions in Brooklyn Heights. Hoyt Street is named after him.)

A bit more searching in google on “Rose Hill” and “Charles Hoyt” led to this hit: an act of the New York State Legislature approving alterations to the City of Brooklyn’s street map. 1851 is when the government actually changed the official Brooklyn maps to match the reality on the ground. The city simply changed the map’s locations for Warren, Baltic, Butler & Douglass Streets, east of Fifth Avenue. The city’s remapped streets matched Hoyt’s Rose Hill map, instead of continuing their straight course from west of Fifth Ave as originally mapped by the city. (Keeping in mind this is before the street NAMES east of Fifth Ave were also changed, which happened later and for completely unrelated reasons.)

You can also see this reference in Dikeman’s Brooklyn Compendium which is THE definitive resource to Brooklyn streets through 1870.

Puzzle solved as to when! The next question is: why?

I don’t think buildings were actually going up in this vicinity in 1851. But since the 1840 newspaper hits show plots were already being sold then, what’s more likely is that someone later in the 1840s eventually realized that their building lots sold off the Rose Hill map didn’t align with the streets on the city map. Since the lots were now dispersed in multiple private hands instead of a single developer, it’d be too complicated to fix the boundaries of individual lots – the easiest fix was just to conform the city map to the facts on the ground.

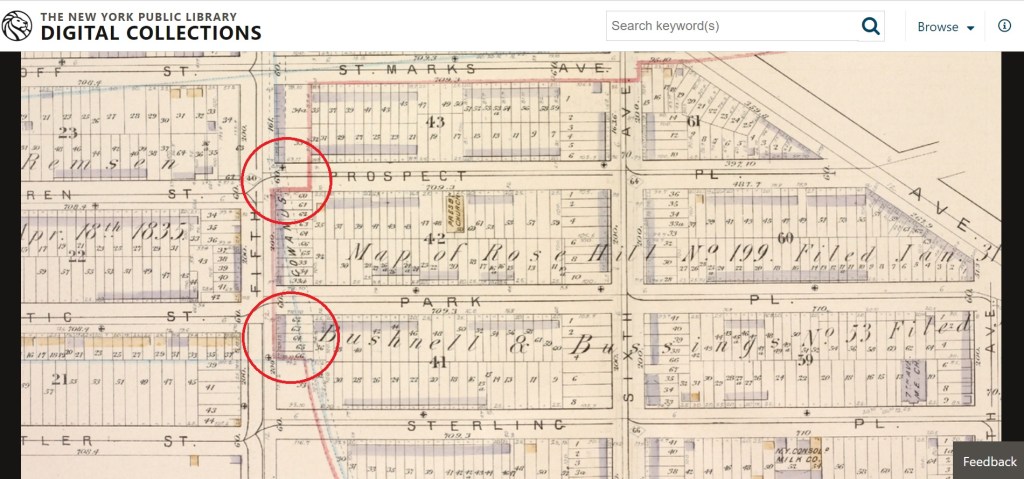

(If you look at the 1880 Hopkins map, you’ll see that there’s an additional italicized label right below “Map of Rose Hill, 1835” – referring to another map filed with the county clerk by “Bushnell and Bussing” in 1855. Probably not much if any building happened here at least until these two new developers came along. But we do know that the the 1851 street grid reconfiguration was attributable to Hoyt’s mapping, because the government action happened before those other speculators came on the scene.)

Now, if you read the 1896 article at face value, it seems to imply that our dog-leg streets coming out of the Rose Hill map ended up that way simply because of sloppy surveying or something like that.

But my guess is that it was intentional.

Look at where I circled the corners on Hoyt’s Rose Hill property:

Hoyt mapped all his lots to about the same depth – sized to fit where these two corners were located in his property – and based his preferred street layout on that lot size. If he had followed the street layout established by the city, some of his lots would be too deep, and some too shallow. Certainly some of the lots along Fifth Ave would’ve been affected, and maybe more. The affected lots would diminish the aggregate value of his development. The extra land in the too-deep lots would be less valuable because in general it wouldn’t be improvable based on the typical building size of the era. And the too-shallow lots would be less valuable because they weren’t big enough for a regular-sized building.

So I think Hoyt just mapped his development to the layout that would maximize his short-term profit. He didn’t care about the long-term effect when it came time to actually open the streets, or put up buildings there. That’d be “someone else’s problem.”

Last question: what was “Rose Hill” exactly?

I think Hoyt picked the name himself, rather than using a pre-existing moniker for a farm here. He only owned the land for a few years before he came up with his subdivision plan. The term doesn’t appear on Butt’s 1846 map – there, the mapmaker simply labeled the land “Charles Hoyt.” And I didn’t find any earlier references to the name being used in this area. (Rose Hill in Manhattan, north of Gramercy Park and west of Kips Bay, is an old neighborhood name there which seems to be completely unrelated, other than the fact that it was developed shortly before the time Hoyt was setting up his Brooklyn subdivision.)

Is it possible Hoyt’s papers and records are stored in an archive somewhere that would shed more light on the name? Perhaps – I looked, and couldn’t find anything. Most likely he did what developers always do – he named the development for marketing appeal. And maybe Hoyt tried to profit off the goodwill of the Manhattan development of the same name. The answer is probably lost to time.

P.S. No one today calls this part of Park Slope “Rose Hill.” (Unlike in Manhattan, where the old name seems to have hung on, at least according to the Extremely Detailed Map Of New York City Neighborhoods put out by The New York Times. About 10% of people feel that little area is best called Rose Hill!)

But all sorts of other old Brooklyn placenames have been resurrected recently, like the Eastern District cheese shop in Greenpoint, the defunct Sixth Ward bar in Boerum Hill, or the also-defunct Freek’s Mill in Gowanus.

Anyone who opens a future Park Slope restaurant or bar called “Rose Hill” or “Rose Hill Farm” owes me a drink 🙂