This Streetscapes feature in The New York Times by Aliza Aufrichtig & me is a visual scroll through 200 years of Brooklyn Heights real estate history. Featuring handwritten deeds, fire insurance maps, land surveys, original ads and lots of vintage & new pix.

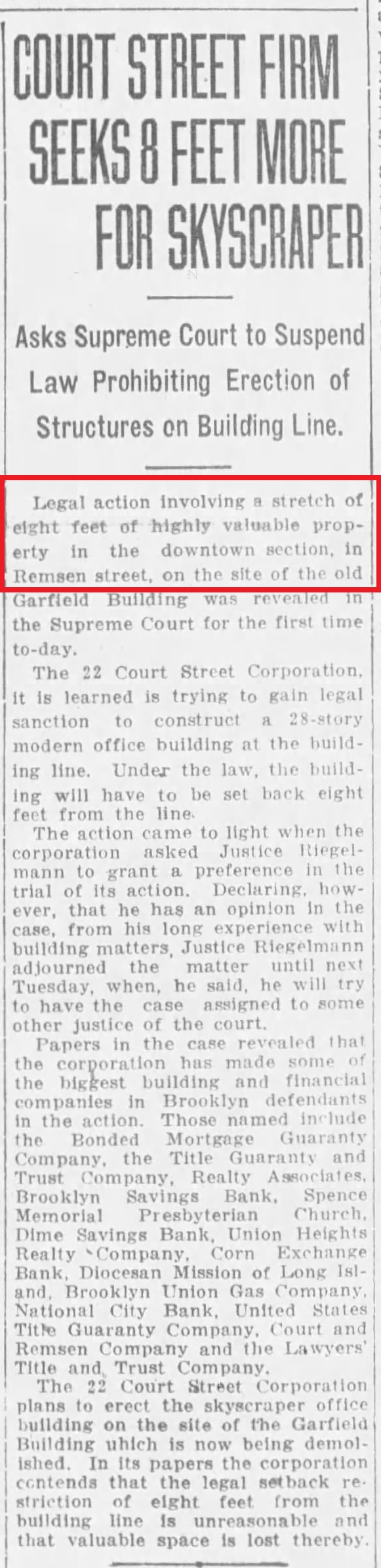

The story is about how private land use rules dating back to the 1820s still dictate the neighborhood’s building development today. We traced the origins of a requirement for 8 feet of open space in front of buildings on a Remsen Street block. One developer says the restriction helped put the kibosh on their $180 million deal!

Here’s even more history & visuals behind the story.

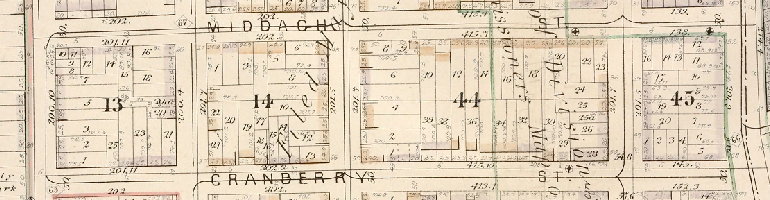

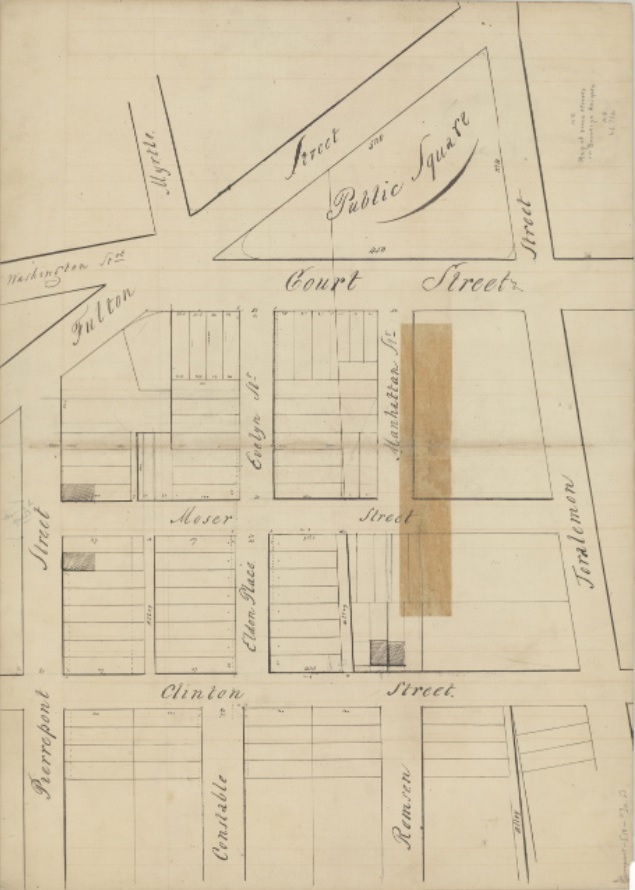

The setting is Remsen Street (between today’s Court and Clinton Streets), and the old St. Francis College campus on the block, now vacant. In this area two hundred years ago, Hezekiah Pierrepont & the Remsen family were still fiddling with maps to lay out streets on their undeveloped land. This block of Remsen St wasn’t even opened yet. Then, Remsen St didn’t run farther east than Clinton St. Instead, proposed streets like Moser, Evelyn, Manhattan, Eldon appeared – on paper. Most of these streets were never opened, or quickly opened and then closed.

At this point in the 1820s, Pierrepont was already advertising 8-foot setbacks for the first Brooklyn Heights streets he developed, like the one he modestly named after himself. (Sarcasm!) Manhattan-centric scholars think David Ruggles innovated by first introducing setbacks for urban developments in 1830s Gramercy Park – but Pierrepont beat him!

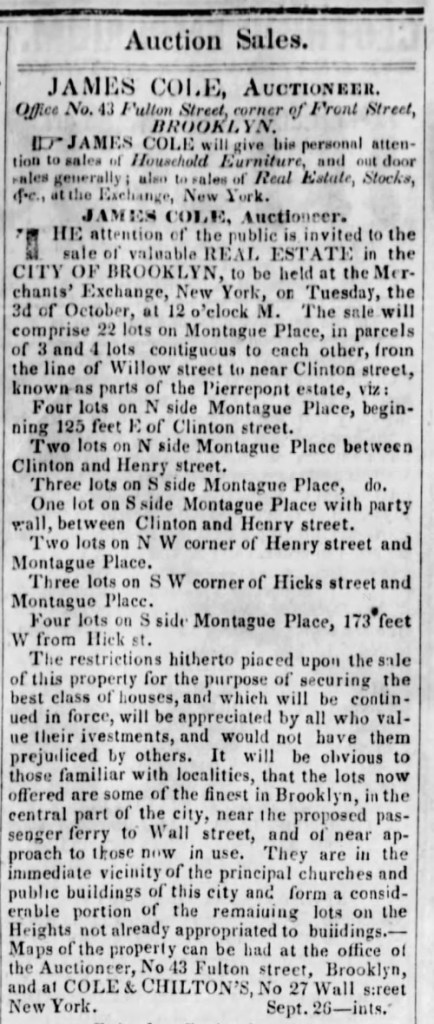

Pierrepont’s ads touted Brooklyn Heights as a “select neighborhood” – but apparently Pierrepont was TOO selective in curating his buyers. Or maybe his prices were just too high. For whatever reason, most of his lots were not sold in his lifetime. It was left to his kids to divvy up a vast estate in the 1840s/50s. Other wealthy Brooklyn Heights land-owners like Harriet Packer, John Prentice & A. A. Low were also active speculators in the neighborhood. They acted as intermediaries between the Pierrepont heirs and builders who were putting up houses on spec.

Auction ads for mid-19th century lot sales by the Pierrepont family mention deed restrictions just like Hezekiah’s original ads from the 1820s. Now, however, they’re saying the quiet part out loud as to the restrictions’ purpose: the covenants “will be appreciated by all who value their investments, and would not have them prejudiced by others.”

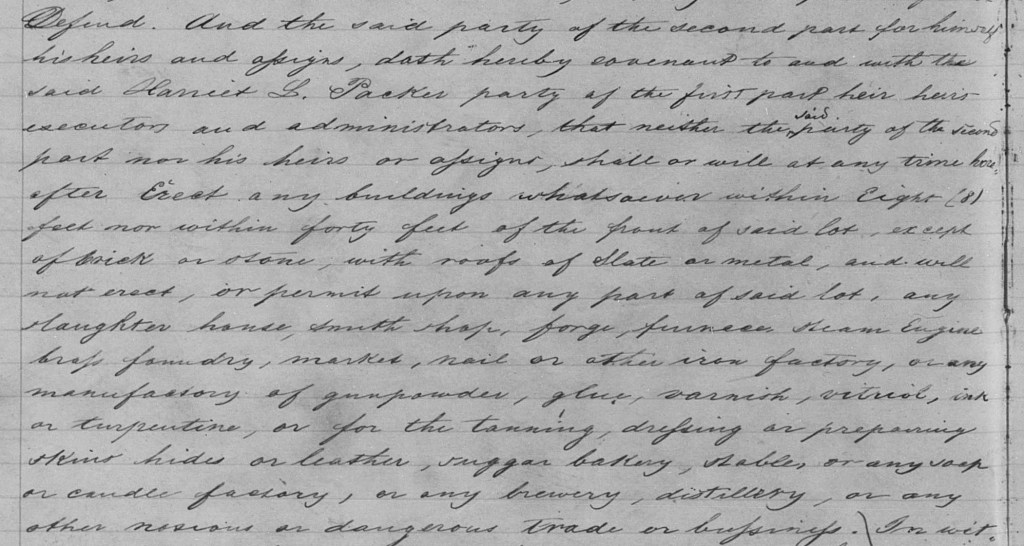

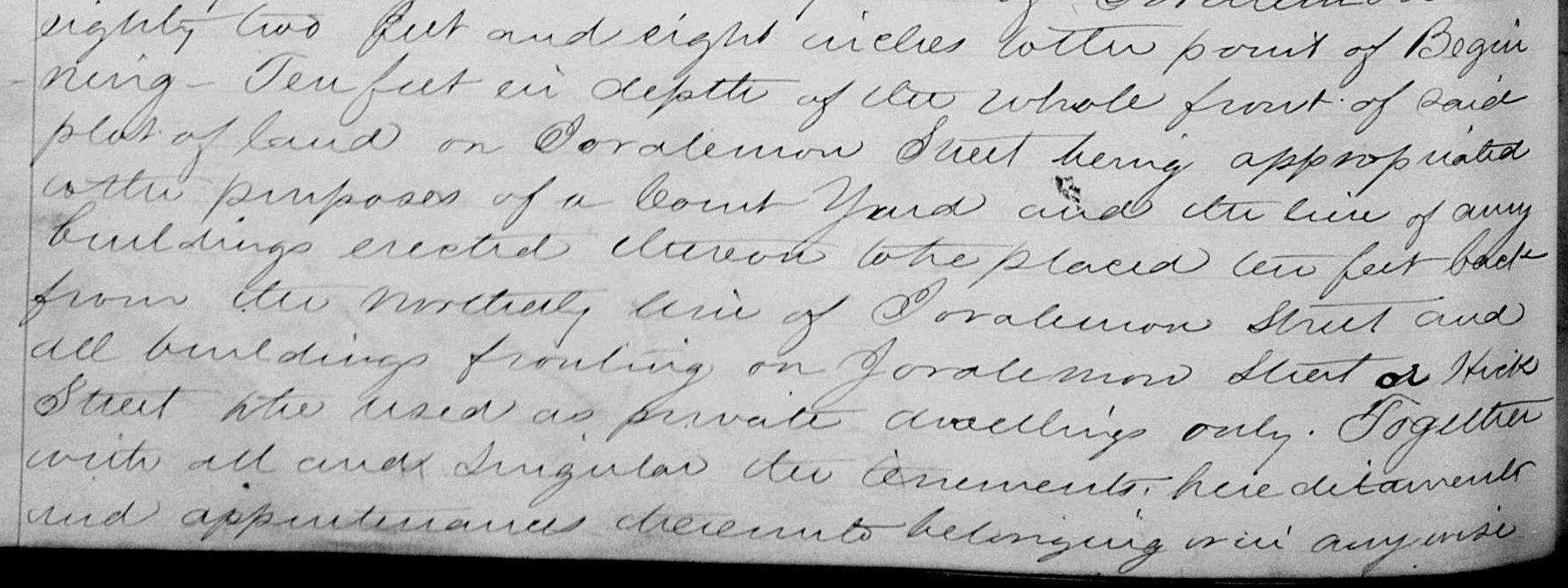

Technically, the deeds granted by the Pierrepont family heirs for the Remsen Street properties at the heart of this story differ from the deeds on other streets granted earlier by Hezekiah Pierrepont himself, or some other deeds granted by Low. Setbacks were still required. However, the use restrictions in these Remsen St deeds merely prevented noxious uses—so this didn’t block the street’s later commercial conversion to offices, the college buildings and so on. In contrast, some of the earlier deeds for other streets explicitly restricted development to private dwellings only, or went beyond conventual noxious uses (tanneries, slaughterhouses, forges, etc.) to also block ordinary commercial/retail uses like taverns & groceries.

Rows of brownstone houses lining Remsen St (where the old St. Francis campus sits empty today) started the block’s first built incarnation in the early 1850s. In front of each house: an 8-foot courtyard. Almost all the houses on the street’s north side were put up by builder John French.

Development of the block’s south side was quirkier. For example, Augustine Boursand built two houses flanking a garden lot & connected by an arcade – a small campus for his “Brooklyn Heights Cadets School of French.” The south side also had a Presbyterian church, and the Brooklyn Gas Light Company headquarters. But eventually, brownstones filled the rest of the block’s south side, too – many of them also built by John French.

Boursand’s 1857 ad lists the old house number…it was later renumbered as 158 Remsen St in 1870.

Some lots on Remsen St escaped the 8-foot setback restriction for…reasons. The Brooklyn Gas Light Company’s Greek temple of an office was unrestricted yet the building honored the setback anyway, to fit in with the browstone houses on the block. But St. Francis College didn’t maintain the setback after they demolished the old Gas Light Company building in the 2000s. You can see that their new library building was built right up to the property line.

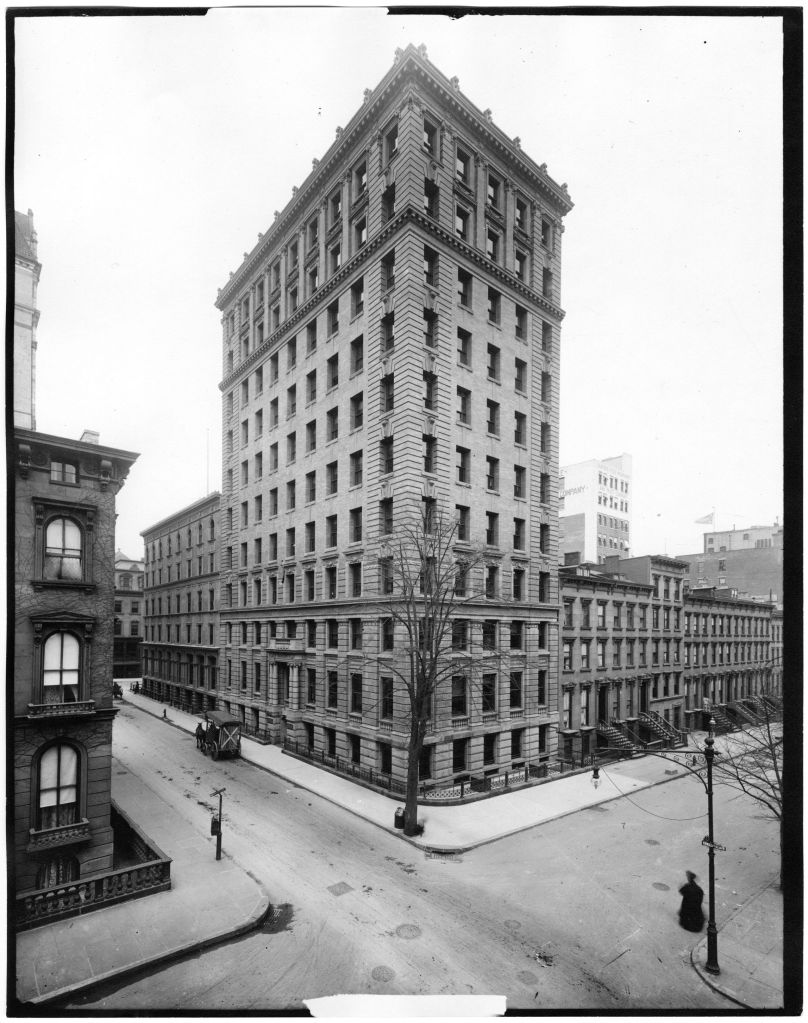

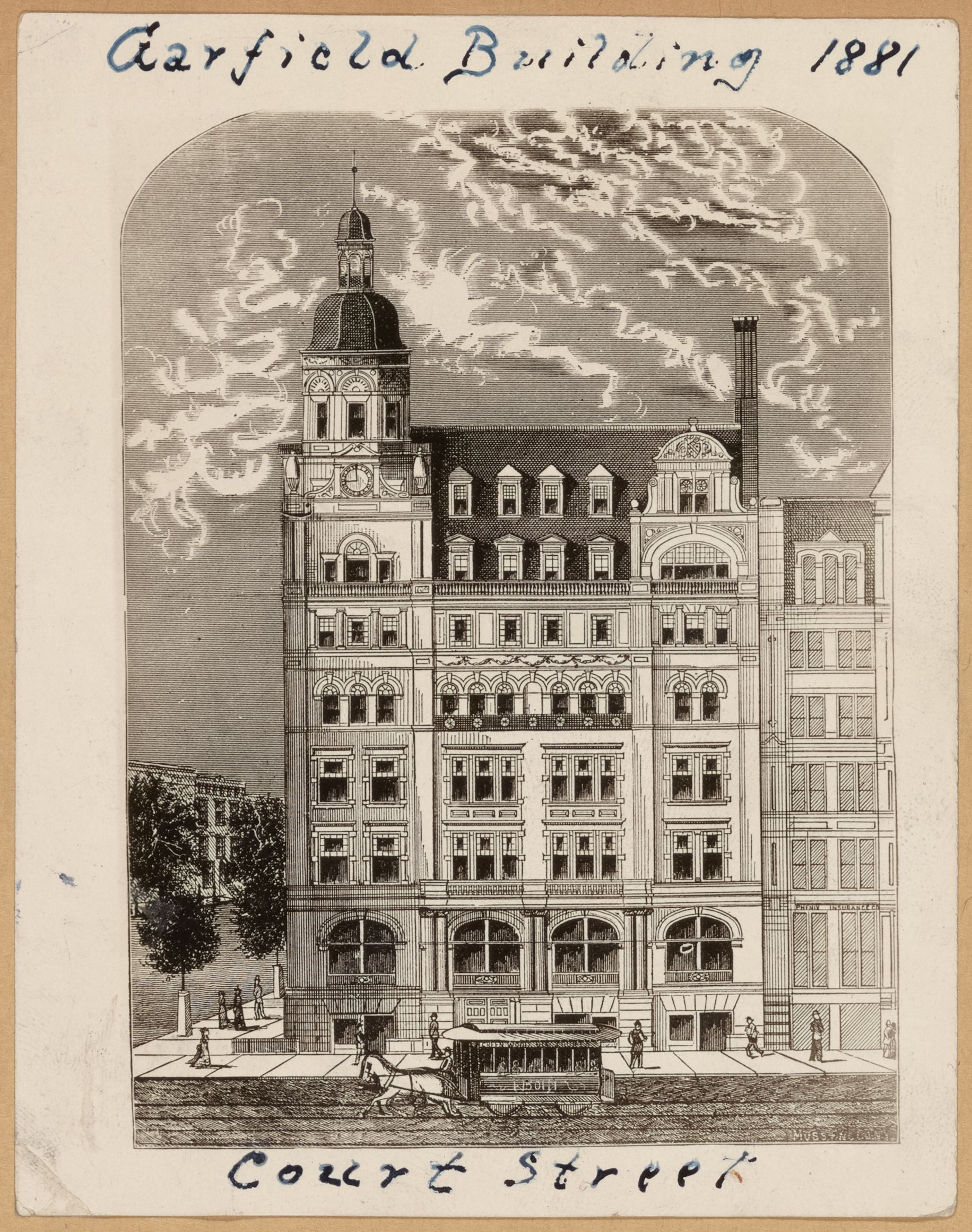

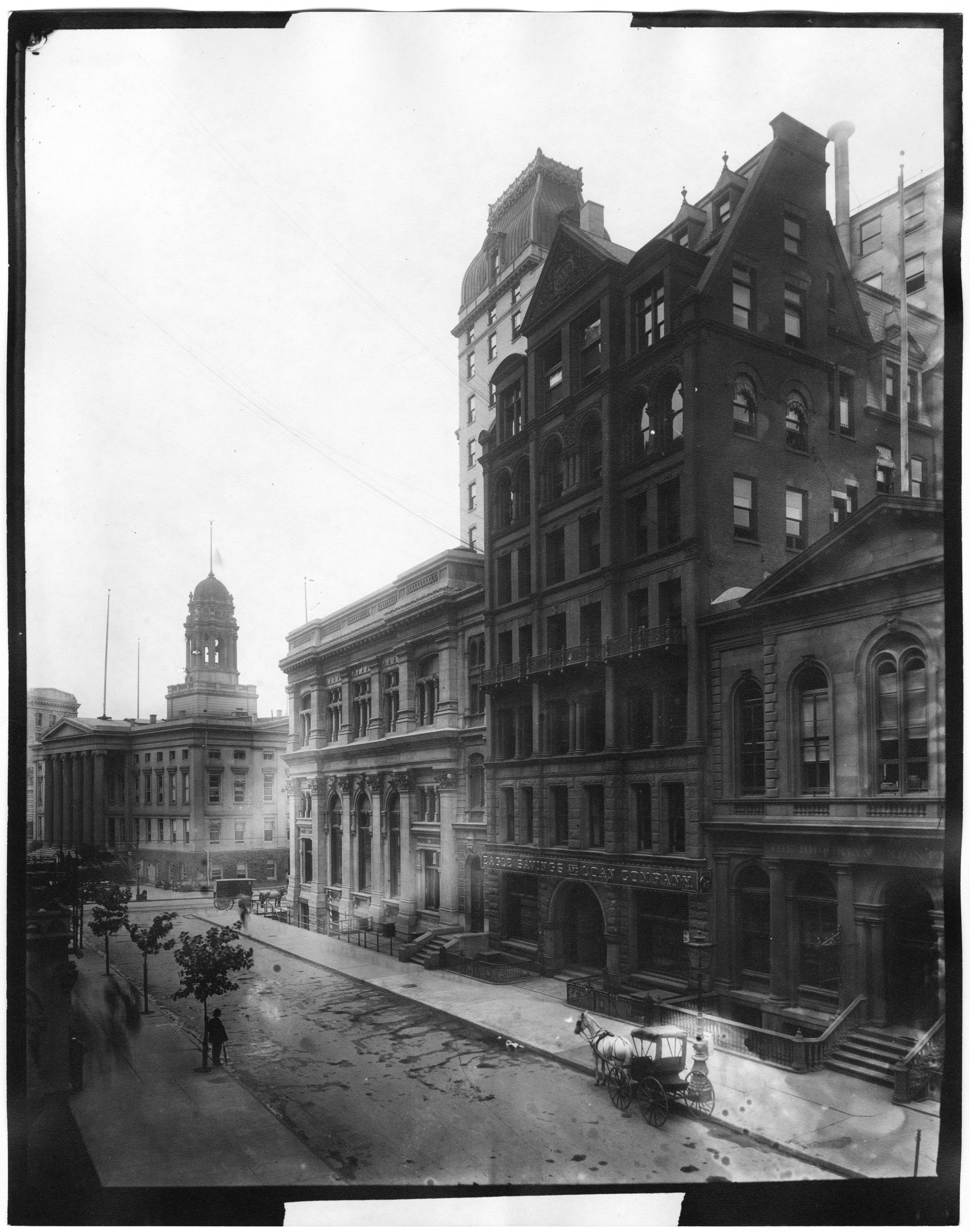

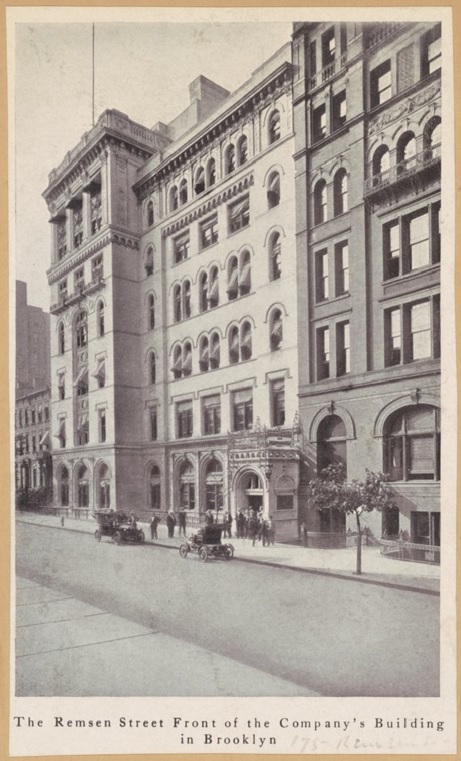

In 1880s, city father A. A. Low (literally: his son Seth was mayor) demolished some Remsen St brownstone houses to make way for his 7-story Garfield Building & 8-story Franklin Building. Though commercial office buildings, each had 8-foot setbacks on Remsen St. The buildings capitalized on the new nexus around City Hall between the Brooklyn Bridge link to Manhattan, and Brooklyn’s upcoming residential neighborhoods farther east and south.

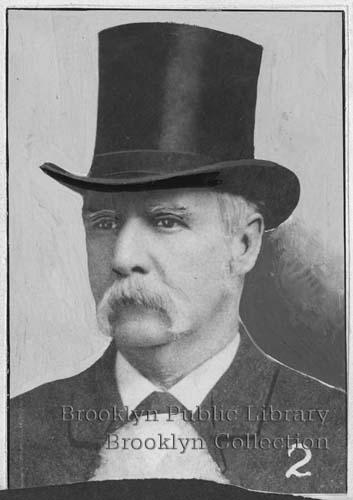

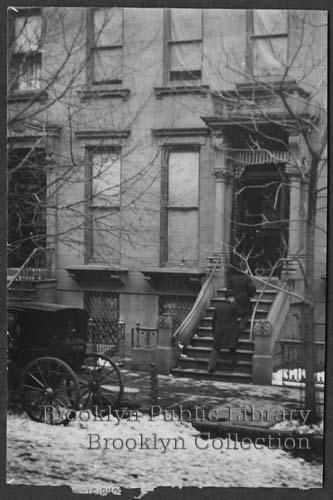

Despite the new tall office buildings put up at the block’s eastern end near Court Street and City Hall, the rest of the street continued to be a wealthy residential zone for a decade or two. Neighbors included Brooklyn Democratic party boss Hugh McLaughlin & City Surveyor Silas Ludlam. But the stage had been set for continued commercial conversion of the block. Here’s McLaughlin and his house at 163 Remsen St.

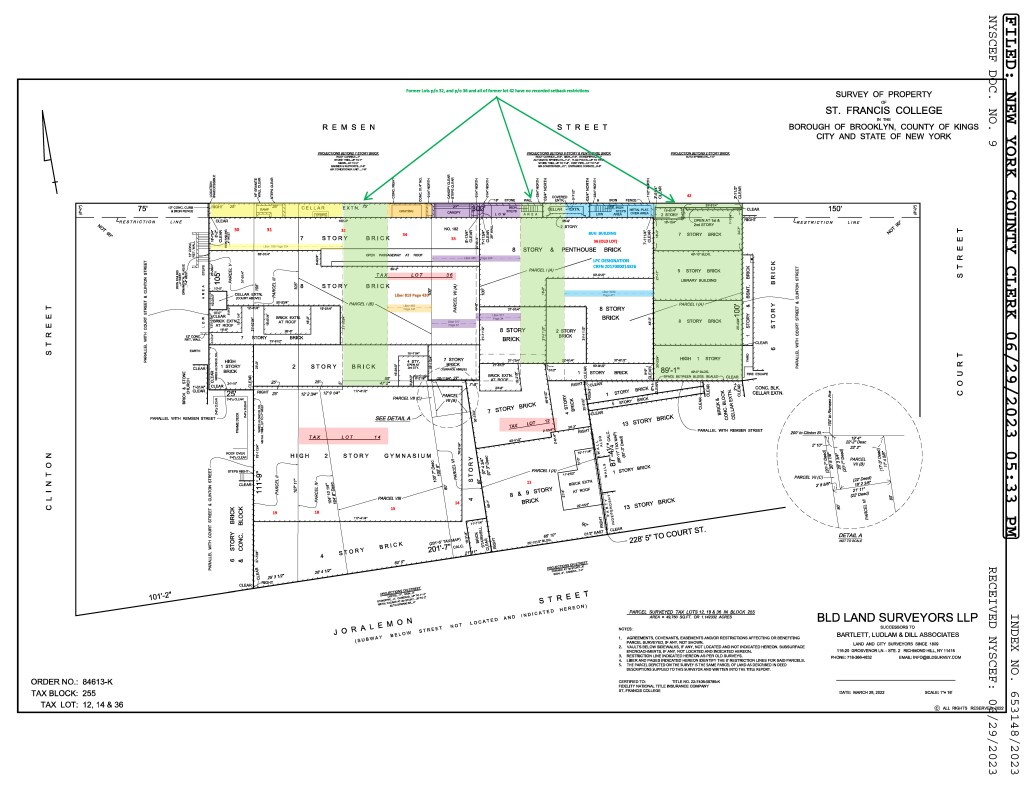

Surveyor Ludlam lived at 176 Remsen St for years. In 1809 his father had founded the firm later known as Bartlett, Ludlam & Dill. They’re still in business today, now known as BLD Land Surveyors. BLD did the survey for Alexico when it tried to buy the St. Francis College campus in 2023 – the site includes Ludlam’s old property!

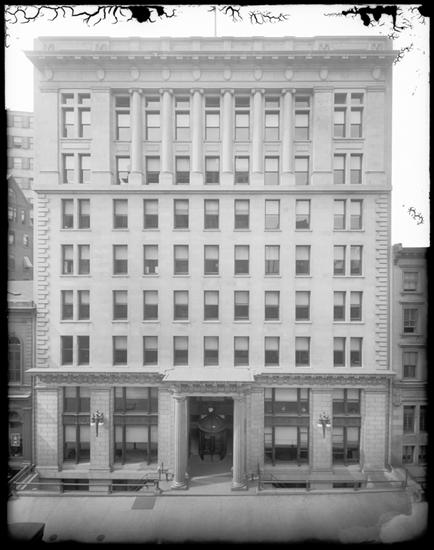

Early 1900s developers tried to challenge Remsen St’s 8-foot setback. In lots where the setback was enshrined in the deeds (and not at sites where a setback was mere custom reflected in the as-built conditions), the developers lost. There were separate debates over whether entrance porticos were allowed to be built in the restricted 8-foot space. It was generally understood that ancillary protrusions off the face of a building like columns or even a stoop were allowed. But some developers tried to stretch the definition of what counted as “ancillary.”

Big commercial buildings continued to go up on Remsen St. Here’s a photo of the Brooklyn City Railroad Building at the northeast corner of Clinton St, built in the early 1900s. The image is Brooklyn’s mid-century demise & renewal in a nutshell—this building came down in the 1930s yet it was still taller than what eventually replaced it on the site today!

Frank Freeman designed 176 Remsen St for the Brooklyn Union Gas Company (BUGCO), c.1914. BUGCO was the successor to the Brooklyn Gas Light Company. Freeman’s building became the central structure in St. Francis College’s former campus. Notice how the architect handled the setback requirement: deep, fenced-in vaults flanking either side of the entrance. This void adhered to the letter to the requirement, which simply prohibited building in that 8-foot space, but not really the spirit, which was intended to provide courtyards or other quasi-public space in front of each original brownstone house. Today the building is landmarked so will remain standing in Rockrose’s redevelopment scheme, 8-foot setback included. (Rockrose’s rendering appears to show the vaults covered and replaced with a landscaped seating area.)

Complicated zoning analysis is required to determine just how much the 8-foot setback really affects future construction at this site. Even if there were no zoning rules, two buildings with the same interior square footage – one with smaller floorplates *due to the setback) but slightly taller, and another with bigger floorplates (if no setback applied) but slighly shorter – aren’t necessarily equivalent in value due to the way the floorplates might be converted into usable space. And on top of that, zoning might restrict the height or other aspects of a building’s bulk, potentially leaving the 8-foot restricted area as a meaningful driver of value reduction. In any case, we do know that Alexico thought the restrictions significantly reduced the site’s $ value – they said so in their legal proceeding with Rockrose and St. Francis College.

Mapping these restrictive covenants is tricky. Alexico thought the sections highlighted in green on this survey of the St. Francis College campus were unrestricted. (Each section corresponds to the original buildings & their lots that make up the current site.) But evidently Alexico’s title search missed a deed. The leftmost green lot actually has a Harriet Packer restriction from 1866.

A reader who left a comment on our article wondered about our point of view on the 8-foot setback restrictions. Was Pierrepont a visionary for using these deed covenants to ensure wide, pleasant streetscapes? Or a villain for trying to keep out the riff-raff from his development? The answer: it’s complicated.

In any case, Pierrepont had a keen eye for how real estate geometry affects value. He certainly did better as a developer than his first Brooklyn venture – the failed Anchor Gin distillery at the foot of Joralemon Street. On the same day in late 1823 when he launched ads for his Brooklyn Heights building lot sales, he advertised he was throwing in the towel on the distillery and offloading it!