140 Clinton Street and 142 Clinton Street Are The Last Two Survivors

The short block of Clinton Street in Brooklyn Heights north of Aitken Place contains one of the most curious rows of houses in the neighborhood. For many years the five houses from 136-144 Clinton Street were known as “Honeymoon Row” – and today only 140 Clinton and 142 Clinton remain as originally built.

The Gothic Revival style Honeymoon Row was built for William Evans in the mid 1850s. Evans was a Brooklyn tailor, operating since the 1840s on Atlantic Street. At that time, the street, since renamed Atlantic Avenue, was one of Brooklyn’s two main commercial thoroughfares, together with lower Fulton Street.

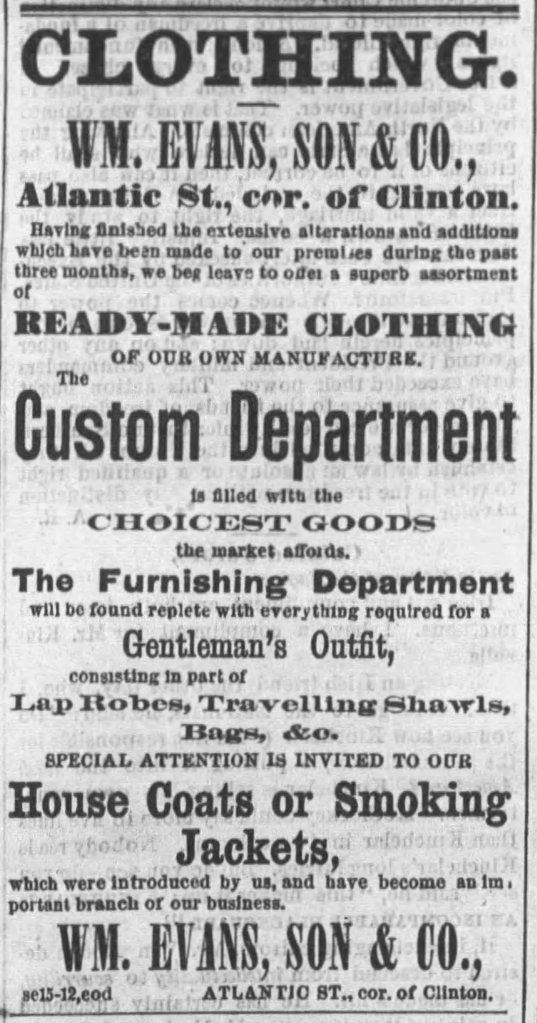

By the 1850s, Evans had his own store as a merchant tailor, at the southwest corner of Atlantic and Clinton Streets. (Home of Tripoli restaurant and Swallow Café today.) Later ads promoted the store’s ready-made clothing as well as its custom department, together with everything necessary to outfit a gentleman: lap robes and travelling shawls (for carriage-riding and driving), and house coats and smoking jackets.

Evidently, Evans was successful. Dabbling in Brooklyn Heights real estate, in the mid 1840s he bought a plot of land on the southeast corner of Schermerhorn and Clinton Streets. He flipped the land to a builder, who put up a row of four houses, one of which (157 Clinton Street) Evans bought for himself.

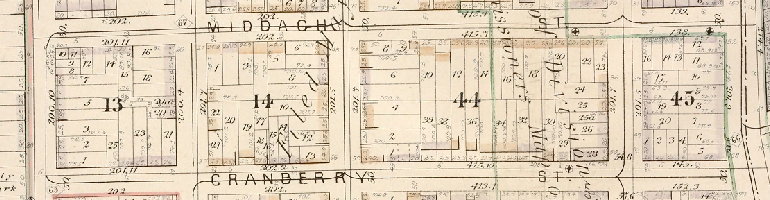

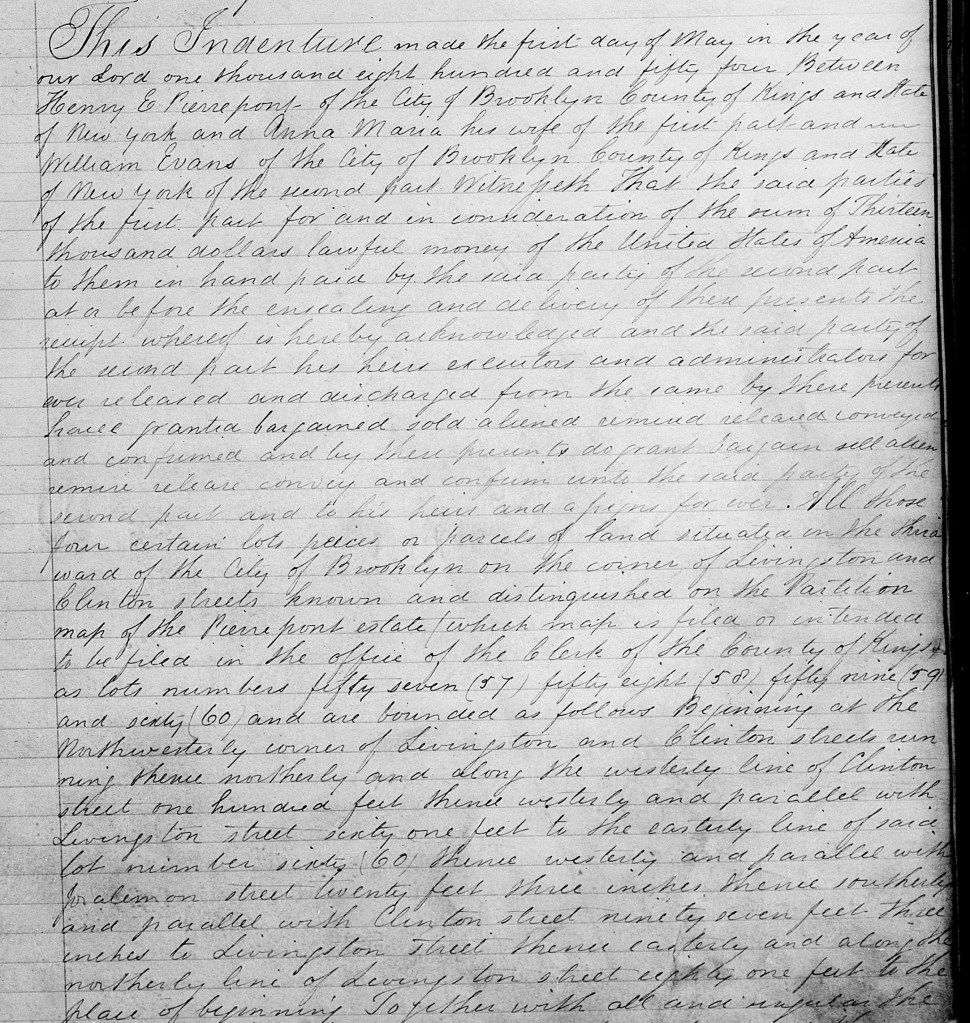

Evans then bought another plot up the block in 1854, at the northwest corner of Clinton and Livingston Streets. Here, Evans put up a row of five relatively small houses, which he kept as investment properties. (He bought the plot from from Henry Evelyn Pierrepont, who was selling the land as four 25’ wide lots. But Evans built five 20’ wide houses instead.) The houses were completed by 1855, when all five were first listed in the Brooklyn city directory, occupied by tenants.

We don’t know who built the houses for Evans. I wouldn’t be surprised at all to learn it was the Chauncey brothers, who by the mid 1850s had already built several rows of houses in the surrounding blocks. The Chaunceys maintained a carpenter shop and builder’s yard on Livingston Street just on the other side of Clinton. An intriguing connection is that the only other group of front-gabled Gothic Revival houses in Brooklyn Heights, like Honeymoon Row, are the ones built by the Chaunceys at 253-257 Henry Street (circa 1849).

Another possibility would be the Dezendorfs, a family of long-time Brooklyn builders. James Dezendorf had built the earlier row of houses on Clinton Street where Evans himself lived. But unless new documentation pops up, it’s just educated guesses to speculate who built the row at Clinton and Livingston for Evans.

Whoever the architect or builder, they took an idiosyncratic approach. Gothic Revival rowhouse design wasn’t a style long for this world. (Or at least in the nineteenth century cities of Brooklyn and New York.)

For American houses generally, the style was popularized by the likes of Alexander Jackson Davis starting in the 1830s. But many of Davis’s quintessential examples were works like Lyndhurst and other country estates in the Hudson Valley. There was a fundamental tension between the country visions of Davis, and urban settings.

Other architects like Davis colleague Richard Upjohn found success applying the Gothic Revival style in city environs by building villas in Brooklyn and its outskirts elsewhere in Kings County. Upjohn designed these kinds of free-standing houses for several clients in Brooklyn Heights like George Hastings (still extant at the corner of Hicks and Pierrepont Streets), and William Packer and George Atwater (both houses demolished). But it was still hard to translate the style into a standard 25 foot x 100 foot “city lot” rowhouse.

For rowhouses, there were two main variants of Gothic Revival in Brooklyn. The one that has survived more successfully, and therefore probably more popular, started with houses that were variations on the basic Greek Revival form, or sometimes transitional Italianate. On that base were layered Gothic details like hooded lintels (“drip moldings”) and a cornice, or sometimes a Gothic-influenced entryway. You see several examples of these across Brooklyn Heights: rows on Henry Street (nos. 117-123), Hicks Street (nos. 131 & 135), Willow Street (nos. 118-122), Clinton Street (nos. 161-167), Willow Place (nos. 2-8).

But even this Gothic Revival variant has the smallest number of surviving 19th century rowhouse examples. Why the style foundered is a bit of a mystery. Maybe because the hooded lintels are sometimes severe; the classical geometry common to many other styles is missing. Whatever the reason, when the Civil War halted most house production in New York City, Gothic Revival didn’t make it to the other side, even as the Italianate style persisted and morphed into new expressions.

The other Gothic Revival rowhouse variant was more ambitious: adaptations of villas or even Carpenter Gothic style wood-frame houses. The telltale sign of this variant is the front-facing gable, with distinctive Gothic bargeboards hanging off. But front-gabled houses aren’t an optimized rowhouse form because they require multiple rooflines, and therefore much less common (at least in Brooklyn).

It’s hard to say whether the front-gabled form’s drawbacks led to rarity, or the fact that they were uncommon led them to be perceived as less desirable. But in any case, there were probably not many built this way, and certainly few have survived. There’s one other Gothic Revival row in Brooklyn Heights with front-facing gables (nos. 253-257 Henry Street), and a few others scattered across Brownstone Brooklyn in Carroll Gardens, Boerum Hill and Wallabout.

The Evans houses on Clinton Street came out in peculiar form, even for Gothic Revival rowhouses. Starting off with the less common gable-front, the front facades were then paired with heavy cast-iron lintels and door surrounds in a particularly baroque take on Italianate design. Today, the sharply contrasting black-painted ironwork and white-painted stucco facades stick out, compared to the softer reds and browns of the surrounding Brooklyn Heights brick and brownstone houses.

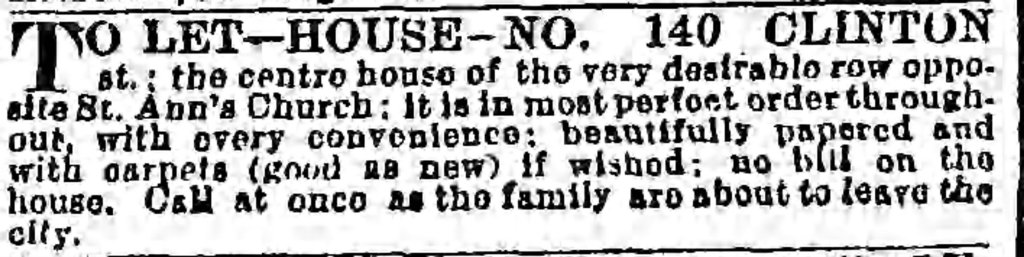

Evans, and later his children, rented out the Honeymoon Row houses. Here are a couple typical classified ads from the 1870s and 1880s.

The houses were sometimes called “cottages” in other ads – a term in 19th century parlance which often referred to small, clapboard houses. In this case, the cottage moniker probably derived from a combination of their relatively small width, compared to other Brooklyn Heights houses, and their quirky front facades that recalled the wooden Carpenter Gothic houses across the U.S. countryside.

Early 20th century newspaper articles referred to the Evans houses as “Honeymoon Row.” Though evidently already long in use among Brooklyn Heights residents, how the phrase got attached to these houses is obscure.

Most of the Evans children were still in diapers when Honeymoon Row was built. Certainly, the name wasn’t analogous to the “Brides Row” on Orange Street, built at a similar time. Unlike Honeymoon Row, the Brides Row houses really were used as residences by the builder’s children (if not actually given as wedding presents).

Here, while William Evans had at least four daughters and three sons, only one child is known to have ever lived in Honeymoon Row for long. His son Henry occupied the corner house at 144 Clinton for a few years in the early 1870s, several years after he’d married. But generally, Honeymoon Row was rented out, and the Evans family lived together first at 157 Clinton and later around the corner at 12 Schermerhorn Street.

A possible origin story for “Honeymoon Row” is that the houses’ atypical, cottage-like appearance gave them a reputation as starter homes. Another theory is that the row’s location directly across from St. Ann’s Church gave rise to a local joke that newlyweds could go “straight from altar to hearth” by renting in an Evans house after their nuptials.

The Evans family had a laundry list of renters for all five houses over the years. Most common were Brooklyn doctors – all of Clinton Street was once known as “Doctors Row.” Manhattan brokers were also well-represented in Honeymoon Row.

No. 140 Clinton certainly has the most famous occupants. Since around 1912, the house was first rented and then later owned by members of the Greeley family, descendants of famous newspaper editor Horace Greeley. And decades before the Greeleys, the house was rented for several years by Emilio Sanchez y Dolz. In the 1870s and early 1800s when he lived at the house, Sanchez y Dolz was known as a ship broker, but was later revealed to be a British spy who worked to destroy the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The Evans family owned Honeymoon Row until 1921. That year, the Evans estate sold the row to various parties. No. 140 Clinton was bought by the Greeley family, who had been living there for almost a decade. Amazingly, 140 Clinton has been owned by only two families over its entire 170 year lifespan!

(You can see how the neighborhood’s desirability declined by the time the Evans family sold in 1921. For example, 142 Clinton had been pocketing $1,100 (!) in annual rent in the 1880s, but the family was only able to get $14,000 for the house when sold four decades later. And on top of that, the family had to give seller financing to the buyers.)

After the 1921 sales, the paths of the other houses in Honeymoon Row diverged wildly. Nos. 136-138 Clinton were occupied for just a few more years, before being knocked down around 1925 as part of the site for the Insurance Building (130 Clinton Street). No. 142 Clinton had a storefront installed on the ground story, but its original façade was later restored and today looks identical to No. 140. The corner house at Livingston Street, 144 Clinton Street, also had a storefront installed, for a Daniel Reeves grocery store. The building was radically altered in the late 1930s by the grocery chain and turned into the little Art Moderne taxpayer building that still stands today (though vacant for many years). Shortly after that, the westernmost block of Livingston Street, at the corner of Honeymoon Row, was renamed Aitken Place.