July 4, 1825 – Cornerstone Laid For The Building That Launched The Brooklyn Museum

The Apprentices’ Library was Brooklyn’s first free library and public reading room. The library association was incorporated in 1824 by Brooklyn benefactors like Augustus Graham. The founders aimed to provide “mechanics, manufacturers, artisans and others” with books and classes. As the name indicated, there was a focus on apprentices and young people who didn’t otherwise have access to free public education.

Over the course of the 19th century, the Apprentices’ Library evolved into a much broader cultural, academic and scientific institution. Through a series of mergers, name changes, expansions and spin-offs, the library was the predecessor of today’s separate Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Children’s Museum, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn Botanic Garden and more.

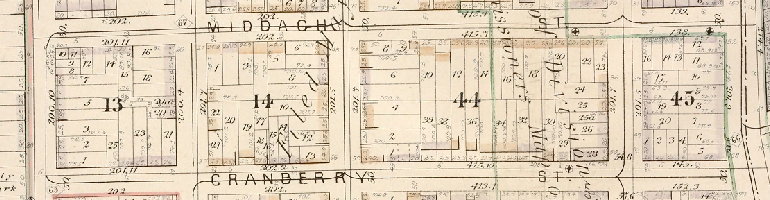

It all started in Brooklyn Heights. In 1825, the Apprentices’ association raised enough money for a dedicated building. They bought land at the southwest corner of Cranberry and Henry Streets, today the site of the Cranlyn apartment. The new library, a modest three-story wooden structure, was built by Gamaliel King, then a young carpenter. King would go on to complete Brooklyn’s City Hall, the Kings County Courthouse and many other of Brooklyn’s great civic buildings put up during its time as an independent city.

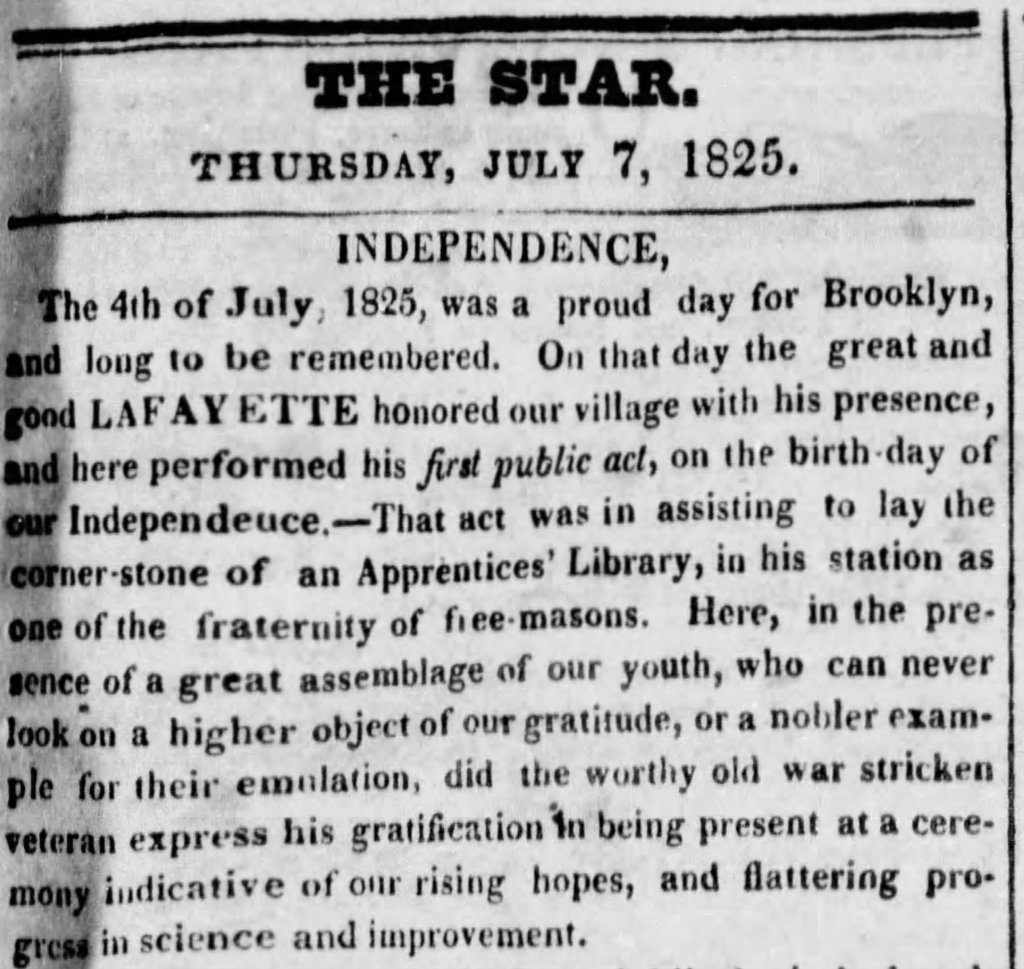

On July 4, 1825, the Apprentices’ Library held a grand cornerstone-laying ceremony for their new building. They led a big parade, with local officials, representatives from mechanics and masonic organizations, and of course, “Apprentices, Sunday Scholars and Youths of the Village,” all marching to the site. The organizers offered a lottery for the students – grand prize was a “golden half-eagle [$5 coin] in a silk purse” and packages of books for each runner-up.

The cornerstone itself contained a time capsule. A later description said the 1825 artifacts were put into a “common pint bottle” and encased in the cornerstone. You can see the outline of the pint bottle, after it was removed in 1858. (More on the cornerstone and its contents below.) The photo comes from the Brooklyn Museum, which still has the cornerstone in its collections today!

The library scored a coup by landing the Marquis de Lafayette to oversee the ceremony. Lafayette, the French general and celebrated hero of the Revolutionary War, was on a year-long “Farewell Tour” of the United States. He agreed to come to Brooklyn Heights on Independence Day, though like any in-demand celebrity, Lafayette “departed for the city” immediately after his official duties were over.

Lafayette wasn’t the only notable in attendance. Six-year-old Walt Whitman was living a couple blocks north on Henry Street on the day of the ceremony, and had lived on Cranberry Street itself the year before. Later in his life, Whitman wrote several descriptions of witnessing Lafayette place the cornerstone. Whitman also claimed that Lafayette picked him up and kissed him, or in some versions, lifted him up so he could get a better view over the older children. Did Lafayette actually interact with Whitman? Or were these recollections an act of creative license by the great poet, or maybe the result of a formative event blurring myth and fact in young Walt’s memory? Nobody knows.

By 1841, the library’s success led it to seek larger quarters in downtown Brooklyn, and the association gave up the little building on Cranberry Street. In the succeeding decade, the city acquired the site, used it as a temporary City Hall until King’s building was finished, and later turned it into an armory. In 1858, the city decided to demolish the old library, and erect its first purpose-built armory.

The revamp was loaded with civic and military symbolism, with the library being Brooklyn’s first de facto public building and its cornerstone laid by the Revolutionary War hero. Another Independence Day cornerstone ceremony was planned, even bigger than 1825, with fireworks, marching bands, and Henry Ward Beecher giving the main speech. The city announced that the pint bottle in the original library cornerstone had been removed and opened to explore the records of 1825.

Whitman himself said the time capsule contained a Village of Brooklyn 1825 directory, a recent issue of the Long-Island Star newspaper and other “relics” inside it. He recounted that in 1858, the old cornerstone and its contents, together with a contemporary time capsule, were placed inside the armory’s foundation near a new cornerstone.

By the end of the 19th century, the regiments occupying the Cranberry Street armory had long moved to bigger buildings deeper in Brooklyn. The city had sold off the old armory. With some expansions, the F. Wesel Company turned the building into a factory for printing equipment.

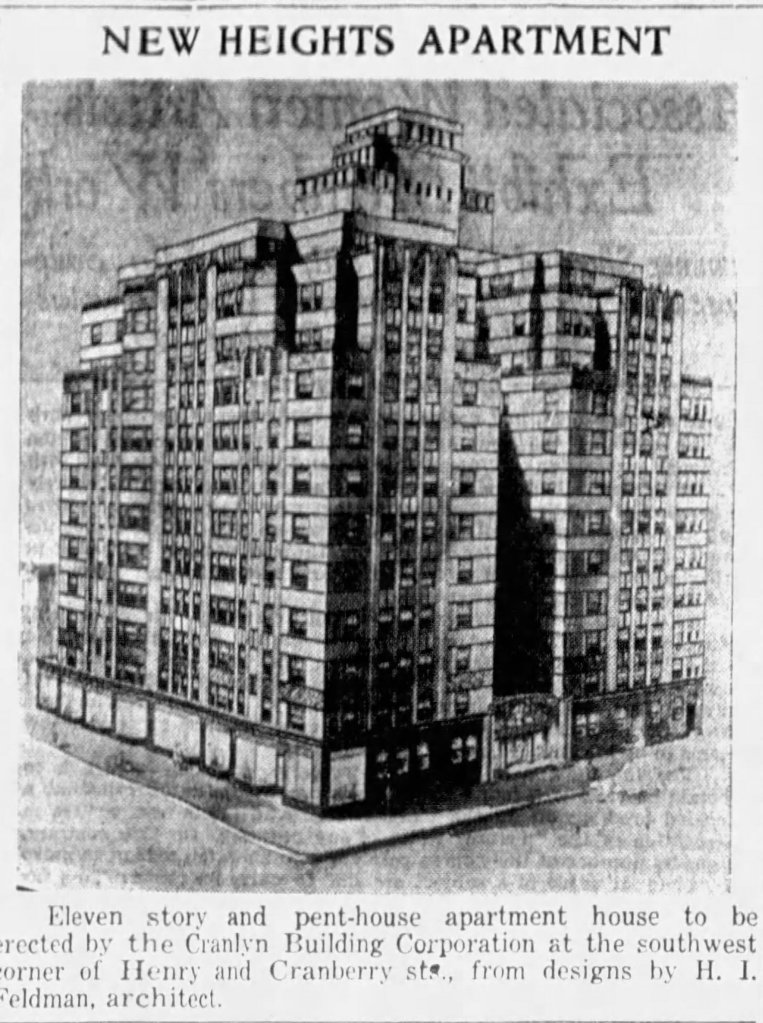

Following the opening of the Clark Street IRT subway in 1919, and the planned IND subway expansion into Brooklyn through the new Cranberry tube in the late 1920s, the large factory became increasingly valuable as a site on which a big residential building could be put up. This value outweighed even the uncertainty of the 1929 stock market crash and the impending Great Depression. In 1930, work started on the Cranlyn, the gorgeous Art Deco apartment building standing there today, even as many other projects across the city had faltered.

The fate of the Apprentices’ Library cornerstone captured the public’s imagination during the Cranlyn’s 1930 construction. One headline blared, “CORNERSTONE IS GOAL OF ARMORY WRECKERS.” The new builders hunted for “the stone touched by the most sacred hands of Lafayette,” as Whitman had written years earlier.

Months later, the Cranlyn builders found their 100-year-old target. Breaking apart the armory foundation, they pulled out a block containing the library’s 1825 cornerstone and a lead box about a cubic foot in size, buried in charcoal and soldered shut. Prying that apart, they pulled out dozens of artifacts from the late 1850s – newspapers, directories, photos, an autograph of President James Buchanan and a piece of the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

But to the surprise and disappointment of 1930 Brooklyn, all the treasure from the 1825 time capsule was missing. No one knows what happened to the precious contents. One possibility is that the older artifacts were never actually re-deposited in 1858, despite reports saying they were. Another scenario, maybe most likely, is that the material “disappeared” in the month after July 4, 1858. It turns out that the armory builders didn’t actually seal the box into the foundation until August, because they wanted to wait to include a newspaper report on the transatlantic cable. Plenty of time for sticky fingers to remove the mementos from a generation earlier!

In yet another twist, it turns out the 1930 opening of the Apprentices’ Library cornerstone time capsule wasn’t the first. In 1882, construction workers at the armory uncovered the old cornerstone and the lead box. They took it to the Brooklyn Institute (immediate predecessor of the Brooklyn Museum) and opened it up. Besides the 1858 records, they found the 1825 Long-Island Star inside but none of the other artifacts from that period. What happened next isn’t recorded, but presumably they resealed everything and put the cornerstone back into the armory, leaving it to be re-discovered by the Cranlyn workers two generations later.